Steve Thaxter- Senior Partner and Principal Adviser

Sovereign Wealth Partner

Investing can be a brutal game that confounds even the brightest minds. As an asset class to invest in, one would expect that cash would be pretty easy to understand. It’s a store of value with little or no volatility. Simple? Actually, it’s a lot more complex. This article explores some of the risks of cash and concludes with some implications for long term investors.

It was billionaire Hedge fund Guru Ray Dalio who coined the phrase “Cash is trash” – making the point that over time, the value of cash is eroded by inflation and it slowly loses its buying power. There’s no disputing this, it’s plain to see that over the long term cash is by far the laggard of all the traditional asset classes.

And Mr Dalio was still calling “Cash is trash” in May 2022, mid way through a brutal year for every major asset class except cash. In fact, in 2022 cash was the only asset class to record a positive return for the year.

So, for cash investors now, where to from here?

After years of money printing, low inflation and falling interest rates, since 2022 we’ve been coming to terms with a new world order. Now we have inflation, quantitative tightening, bank failures overseas, higher interest rates, wage growth and Central Bankers around the world caught in the spotlight. They really don’t know if they can get inflation back under control without causing a brutal recession. The investing paradigm has changed and to understand the outlook for cash we need to go back to basics.

What is cash and how safe is it?

Cash is a medium of exchange. It consists of notes and coins of a particular currency, manufactured by a central bank, authorised and backed by a government. We don’t need to stash our money under the bed, we can easily convert it to deposits at banks and other authorised deposit taking institutions (“ADIs”). When we do so we even get paid interest for our trouble. The interest we get is usually less than inflation (hence Mr Dalio’s view that “cash is trash”), but it certainly helps. Right now, with a little shopping around we can find “at call” accounts and term deposits in Australia paying 4% or more.

So far so good. But look deeper and you realise the system relies on confidence: confidence that cash is actually worth something and confidence in the banking system itself.

Modern cash is technically “fiat” money, in that it is not backed by any commodity. “Fiat” is a Latin word meaning “let it be done” and was used in the sense of an official order or decree. Major currencies have been untethered to commodities since around 1971 when the US defaulted against and abandoned the gold standard. Instead, every major currency relies on the credibility of the issuer, the noble pictures on its banknotes and a vague government decree that the paper is actually worth having.

And because it’s not anchored to anything physical, fiat money is elastic. Any government can print as much of its own currency as it likes. This means governments can run perennial budget deficits and borrow more and more. Everyone wants more money so elastic money creation is politically expedient until some sort of tipping point is reached and its value is questioned. Every tipping point is elusive, but a symptom of a currency in trouble is persistent, rising inflation. Finally, when there’s little confidence in a nation’s finances, people switch to other currencies and either an abrupt devaluation is attempted or hyperinflation takes over. For a currency this is usually the death knell.

The famous examples are Germany’s Weimar Republic, Venezuela and Zimbabwe. More recently Turkey, Argentina, Sudan, Yemen, Iran and Sri Lanka have entered hyperinflation. Citizens of those countries and holders of those currencies face a bleak outcome.

What’s disconcerting for holders of major currencies is that studies have concluded that every fiat currency has a limited lifespan. Including the strongest, which today is the US dollar. This is because the elastic nature of money creation will gradually debase each currency as the underlying economies go through the boom, bust and credit cycle.

Dalio has estimated that only 20% of the currencies that have existed in the last 250 years still remain. He argues that the natural order of things is that even the US dollar will collapse, although no one knows when. The inherent flaws of traditional currencies have contributed to the rise of cryptocurrencies, although the risks in that new asset class have proven to be underestimated and painful for many.

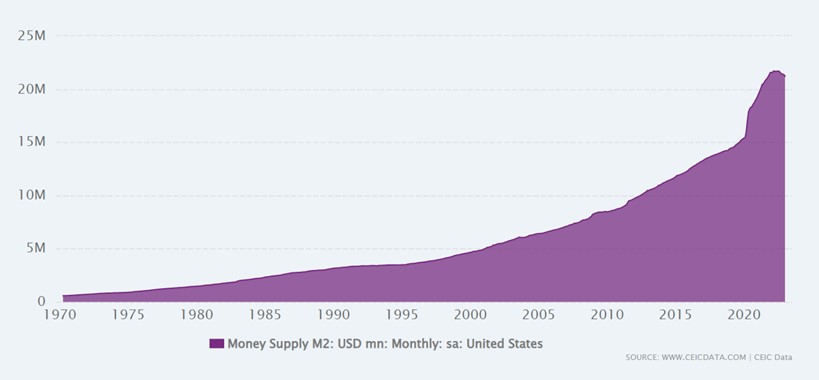

Money Supply in the US

(source CEIC data)

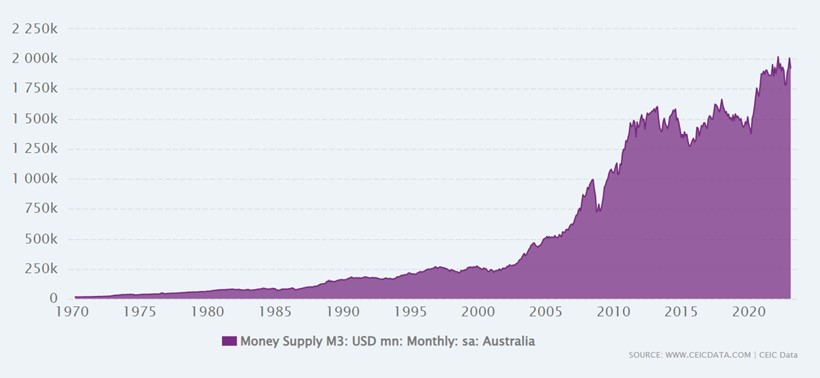

Money Supply in Australia

(source CEIC data)

We’ve written before on whether gold is a safer asset class and the same considerations apply for other commodities such as silver, oil and copper.

Banking is elastic too – the bank holding your cash on deposit is allowed to give about 85% of it to other people in the form of loans. Those loans go out, the money comes back as deposits to different accounts and is then lent out again, creating new money through the money multiplier effect.

This works well in normal times (in fact it’s credited as one of the major sources of wealth and prosperity in modern times) but it’s no good if everyone wants their deposit back at the same time. Like when there’s no confidence in a particular bank. This year some fairly high profile banks have failed overseas, such as Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic Bank, Signature Bank and Credit Suisse. In each case the failure was caused by a combination of poor management and a business model that didn’t suit the new economic paradigm.

Thankfully Australian banks have largely escaped a loss of confidence, even though their share prices have eased back. But the reality remains that no bank can survive a run on its deposits without getting bailed out by a bigger bank.

Since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 Australian banks and other ADIs have had the backstop of depositors having the first $250,000 of their deposits at each ADI guaranteed by the government.

Returning to the concept of elastic money, raising interest rates in the fight against inflation discourages new lending at the margin and makes it more expensive to issue and service debt. The elastic stretches in new directions and the value of everything is called into question.

The chart above shows that the US has moved into a contraction in money supply for the first time in modern history. The US Fed reserve is trying to engineer a return to sustainable inflation levels without bringing about a brutal recession. One piece of good news in Australia is that present forecasts are for a budget surplus this financial year (although not for next year) which will take some pressure off the national debt for a little while.

Wealth Management and cash

Returning to the wealth management implications of cash as an investment class we should remember that:

- Against all other asset classes, cash has performed the worst over long periods. The implication is that long term investors should only hold modest cash balances over the long term.

- Cash is elastic and currencies tend to have a limited life. The implication is that investors should seek currencies that are likely to hold their value against others over the longer term and at least consider diversifying their currency holdings. In the meantime, we need to keep a close eye on the home front. It is important that Australia maintain its AAA credit rating and regulate its banks carefully.

- Cash is king in moments of crisis and uncertainty – good examples of this were the precipitous falls in other assets during the global financial crisis in 2008 and COVID in March 2020. For this reason there is a good argument for holding a cash reserve:

- to take advantage of buying opportunities in times of market panic

- to prevent the need to liquidate other assets when prices are down and

- for any unforeseen personal emergencies.

- If your source of income is your portfolio (rather than earned income from your job) you’ll need to maintain a higher cash buffer. This is because in a downturn you’re unable to put off selling portfolio assets just because the market is down. Think in terms of a cash balance being no less than a certain multiple of monthly spending. Some advisers recommend 18 months or more for retirees.

- Investors with over $250,000 in cash should bear in mind the $250,000 government deposit guarantee works at a per person/entity, per ADI basis. This isn’t as simple as it seems since some ADI’s have many trading names. Consider:

- BankWest is a different trading name for the Commonwealth Bank (CBA).

- UBank is a different trading name for National Australia Bank (NAB).

- ME bank is a different trading name for the Bank of Queensland (BOQ).

- Bank of Melbourne, BankSA and St George Bank are different trading names for the Westpac Banking Corporation (WBC).

- There are a dozen different trading names for Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited.

- What really moves the markets are the things that happen that weren’t predicted by the experts. That’s why the patchwork quilt in this chart is so colourful. In our view, diversification remains the biggest free lunch in investing. Having a spread across all viable asset classes is more likely to deliver an investment journey that’s sustainable. Right now, after the poor returns of 2022 and the credit related stresses of today, our view is that several asset classes are better priced than they have been for years. That’s great, but the risks are high. The new world order is revealing itself in unfamiliar ways.

- Irrespective of what the investment markets serve up, your cashflow needs, your investment timeframe and your risk tolerance is unique to you. These will continue to have a profound bearing on how much cash you should hold.